What’s in a Name: Football vs. Soccer

How a mob game entered English schools and became the sport we know and love

Thank you to everyone who read the first post of ‘Print the Legend,’ the reception has been very encouraging. I’d also like to give a special thanks to those of you who subscribed! If you haven’t subscribed yet, let me tell you this journey is just beginning, the truly good stuff is coming, and the best to keep up with it is to click the subscribe button below so you can get all new posts directly in your inbox. Alright, that’s enough self-promotion, let’s get to the soccer.

Today’s installment is meant to address the elephant in the room. Not only are Americans notorious for sidelining the most popular sport in the world, and not only do they choose to call it something else from the rest of the world, but they also have the gull to take this other ridiculous sport that only they care about and call it Football even though it’s not even played with your feet! What is wrong with these crazy gringos? Why can’t they just run a couple kilometers, reach a comfortable temperature of 20 degrees Celsius and enjoy the football match like the rest of us? Where the hell did the name soccer even come from?!

If you search the word “football” on Wikipedia (which you probably never have because why would you) you will see that the article is dedicated neither to soccer nor “American” football. Instead, Wikipedia diplomatically informs us that the term “football” describes “a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal.” Not bad as a first attempt at a definition, but not quite satisfying either. Yes, it is true that after scoring a touchdown in American Football, a player will then kick the ball between two posts in order to earn extra points, but that kick is optional, and the bulk of the game is played by grabbing the ball with your hands as tight as you can. As far as popular American sports go, Hockey feels much more similar to Soccer in gameplay and overall strategy than Football. Claiming that “kicking a ball” is enough to bundle these two sports together will not convince anyone. And yet, looking at the history reveals that Soccer and Football are indeed siblings - or at the very least cousins.

Shortly after I started researching the history of soccer, I came across a piece of information that quickly transformed the opinion, held for most of my lifetime, that America’s insistence on calling their favorite game “football” was so ridiculous it bordered on the criminal. The big realization is this: the name “football” was not coined to describe a game that is played with your feet, but a game that is played on your feet. Aren’t all sports played on your feet? That might be the case nowadays, but not if you go back and consider who was playing sports in Medieval England, when the game was first played. The earliest available records suggest a prototypical version of football/soccer was played in the British Isles as early as the 15th Century. Notably, this was a peasant’s game that stood in contrast to the nobility’s recreational pass-times, like fox-hunting and polo, which involved horseback riding. The term “football,” then, holds quite a bit of judgment - it was coined to reflect the rough and rowdy nature of a game where two whole villages walked out onto a field and proceeded to chase a primitive version of a ball (probably a pig’s bladder) in chaotic fashion. A “football match” in those times probably looked more like a violent brawl than any kind of organized sport. If there were any rules, they were guaranteed to vary from one town to another, much like kids from different neighborhoods might have different ways of playing tag, or how every family modifies the rules of Monopoly to their will. It was chaotic and violent, but also, unmistakably, a game of the people.

This anarchic period ended when the rich got it into their minds that they could turn chaotic brawls into a tool for education. According to Jonathan Wilson’s great book Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Soccer Tactics, the 19th Century brought about an existential crisis among Victorian elites who could sense that the British Empire was entering its decline. The source of decline was believed to be a softening in the national character, so it became imperative to instill proper conduct and moral fortitude in every young gentleman in order to maintain English superiority. It was at this time that public schools discovered that sports could play an essential role in the moral education of their students. Now, public schools are, confusingly, the British term for what we in the rest of the world would call private schools. These were expensive, elite institutions where the nobility and aristocracy would send their young lads to get a proper education, which basically meant being beaten mercilessly until they learn to suppress all of their emotions. Wilson paints the full picture when he explains: “Team sports, it was thought, were to be promoted because they discouraged solipsism, and solipsism allowed masturbation to flourish, and there could be nothing more debilitating than that.”

In order for the mob game known as “football” to become an educational tool appropriate for fancy lads it was necessary to write down some rules. In the early days each school - much like medieval towns, neighborhood kids, and board-game-playing families - developed its own set of rules based on their particular circumstances. As Wilson tells it, “[a]t Cheltenham and Rugby, for instance, with their wide, open fields, the game differed little from the mob game,” while “in the cloisters of Charterhouse and Westminster [...] such rough-and-tumble play would have led to broken bones.” It’s at this moment that the first big schism of Football occurred. Rugby School went ahead and codified the rules of the sport that would become Rugby Football. Meanwhile, it was at the cloistered schools that tackling was discouraged and an emphasis was placed on dribbling the ball up the court using one’s feet, which resulted in what we now called Association Football.1

Notice the fact that both variations of the game have the word “football” in their name. The word “football” had been used interchangeably to describe any of these village mob games and/or the codified versions that developed in the public schools. With this backstory, it becomes much easier to imagine the origins of the American usage of the word “football” to describe their disgusting version of the game. America’s first encounters with football were likely slightly smaller versions of the mob game that existed since medieval England, with the rules being codified in America’s top colleges and universities much like the public schools codified the game back in Britain. For whatever reason, the Americans preferred a version closer to Rugby. Soon enough, there was a whole system of intramural competitions between colleges, and isolated from the development of the parallel games in Britain, Americans ended up feeling totally comfortable and unbothered to call the game they developed, simply, “football.”

But what about the term “soccer”? To answer that one we have to go back to England, and to the time when different versions of the sport began to be codified in rule books. After a while, all the many different versions start to coalesce into two broad categories: those that allow picking up the ball and those that don’t. At that point, you have to be able to differentiate the two, lest you advertise a Football game only to end up with a bunch of fans disappointed to find themselves at a Rugby match. So, you drop the part of the name that is the same and you start calling one of them Rugby and the other one… Association? No, that sounds terrible. Well, the Rugby folks playfully call their “Rugger,” so maybe instead of saying Association we can just say… Associater? Associer? Assoccer? Almost, let’s just drop the “A.” A-ha! Soccer! It was a bumpy road getting there, but we got there nonetheless.

Despite the invention of the term “soccer,” British culture evolved to distinguish between the two most popular codified versions of the mob game as “rugby” and “football.” The term “soccer”, however, is still used in Britain to this day, though it is most often deployed when a sports writer or commentator wants to make an alliterative comment, like exclaiming “spectacular soccer!” when they’ve deployed “fantastic football!” too many times. Soccer was played in the United States throughout this period, but mostly in amateurish contests whose popularity paled in comparison to American collegiate football. In this context, also calling the significantly less popular sport “football” was kind of confusing, and that’s basically how the term “soccer” caught on.

Now, I’m from South America. Of course I hated the term “soccer” the minute I heard it, and to this day I feel a tiny shiver every time I say it myself. Learning about the name’s origins, however, did change my perspective on it quite a bit. Is the abbreviation of Association into Soccer a little far-fetched? Definitely, and that’s probably why most people ignored it and chose to call it “football” instead, but we must recognize that it is far from a random name invented by the Americans as many people around the world tend to believe. It’s also worth remembering the U.S. isn’t the only part of the world that has its own name for the sport. There are literal translations of the name, like the German “Fussball” (pronounced Foos-bahl) or the less common Spanish term “Balonpie” (literally “ball” and “foot”). Then there’s the Italians, who use the term “Calcio,” a name that derives from another medieval game played with a ball in, this time in Renaissance-era Florence, and whose name was revived in the thirties as one of Benito Mussollin’s many attempts to use Soccer to further Italian Nationalism (more on that in a couple weeks.) Then there’s also the fact that most Hispanic countries use the term “Futbol,” just as speakers of Portuguese use the term “Futebol,” and it’s not like those words mean anything in either of those languages when taken literally. In short, I’ve learned to stop worrying about names, and focus on the good stuff, which is the game itself.

The Origins of International Soccer

As I wrote about in the introductory essay for this project, the history of Soccer is the history of regional differences and National identities expressed through individual and collective styles of play. At its inception, Soccer embodied the ideals of its English parentage: perseverance, stubbornness, and a blinding sense of superiority. These values are clearly reflected in the way English teams chose to play soccer throughout the 19th Century - keeping the ball close to their feet and simply charging forward, putting their belief in manly fortitude ahead of any kind of strategic consideration. Jonathan Wilson describes this early English style as follows: “the game was all about dribbling; passing, cooperation, and defending were perceived as somehow inferior. Head-down charging, certainly, was preferred to thinking, a manifestation, some would say, of the English attitude to life in general.”

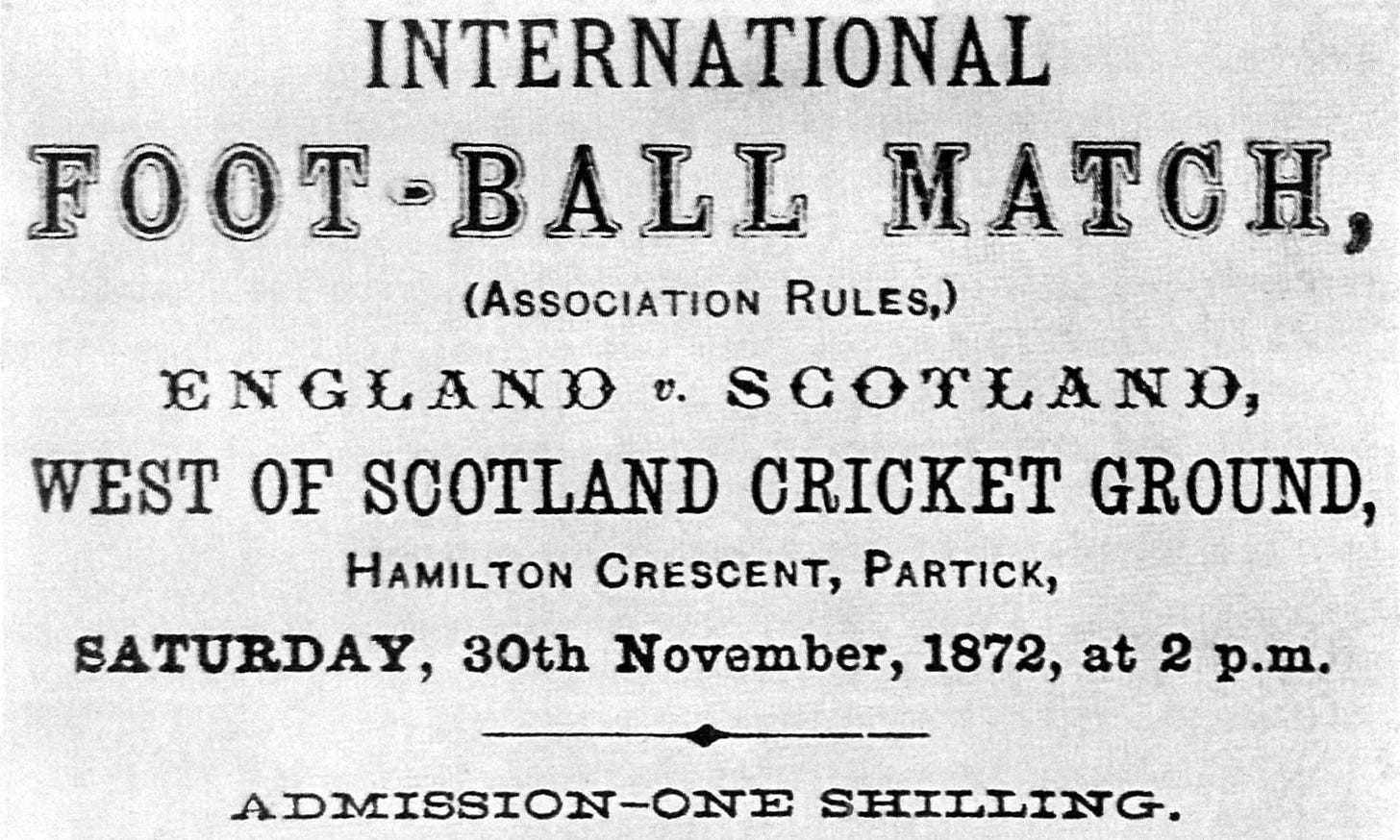

Much like the cavalry generals of World War I, whose 19th Century training led them to believe that wars are won by the army with the most vigorous spirit, and who charged into battle to realize, only too late, that men on horseback don’t stand a chance against machine guns, the English way of playing soccer crumbled as soon as it was confronted by a team who was willing to play the game through strategy rather than principle. In a typical bit of British self-centeredness, the first “international” match in the history of soccer was played between England and Scotland, on November 30, 1872 in Glasgow. In an even more typical turn, the match ended in a 0-0 draw. Despite the score line, the match was perceived as a big moral victory for Scotland and an even bigger embarrassment for the English, who had been outwitted at their own game.

England had both a larger pool of players to choose from and a physical advantage - their players were literally larger and stronger than the Scots. But the Scottish team wisely avoided charging against the English in their “kick and chase” style, instead they did something totally shocking: they passed the ball between each other before the opposition could get to it. The English were appalled to encounter sportsmen who would do something as ungentlemanly as passing the ball, but their moral outrage could not hide the fact that they were simply unable to keep up against a team that had clearly found a much more effective way of moving the ball toward goal. What’s more, while the English were physically superior, dribbling the ball up and down the pitch is far more tiring than kicking it to your team-mate, and letting the ball do the running for you.

This was the first time, but certainly not the last time, that England came against international opposition and learned the hard way that their way of playing the game had become hopelessly outmoded. To be clear, the Scots did not come up with the idea of passing the ball specifically for the match against England - by all accounts passing had been a part of the game north of the border for quite a while by then - but there is something romantic in the fact that the very first international match perfectly captures the kind of historiography that I’m trying to develop with this project: the very first time two Nations faced each other, the match was decided by how each country decided to play the game, and those styles of play were reflective of their respective national characters.

This first international match also reflects one of the most distinctive features of soccer as a sport, and one that can frustrate people who are used to watching sports in which the winner can be declared to be better than the opposition. Anecdotally, the three complaints I hear most from people who are unfamiliar with soccer are: there are not enough goals per match, it’s ridiculous that a match can end in a tie, and it’s frustrating that the better team doesn’t always win. For those who love soccer, however, this last factor is a bug but a feature. As soccer analytics specialist Alex Stewart put it in the Tifo Football Podcast: “(Soccer) doesn’t follow a script in the sense that the best or the most exciting team necessarily wins, but I think it does follow script in the sense that a team who organizes themselves, who thinks carefully about how their opposition are gonna play and then reacts to that, can often win against a team who’s better.”

⚽⚽⚽

International soccer flourished in Great Britain, but in a predictably solipsistic manner. England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland (later Northern Ireland) all developed their own national teams, and soon enough the “British Home Championship” was established. This was a yearly tournament in which the four Nations played each other. While the British played each other, soccer crossed both the English Channel and the Atlantic Ocean, and seemed to gain enormous popularity wherever it went. By the turn of the 20th Century, soccer was played throughout most of continental Europe, and teams were eager to create a regulating body designed to self-govern the rules of soccer on an international level. On May 21, 1904, several European federations got together in Paris and founded the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (International Federation of Association Football, or FIFA).

None of the British Home Nations were among the founders of FIFA, though they begrudgingly joined a year later, probably with the intention of keeping this new group’s influence in check. The English Football Association was completely opposed to the idea of an international body that could decide how they, the inventors of soccer, should play the game. This sense of English superiority was only exacerbated by the fact that virtually every encounter between England and teams from outside the British Isles ended in an English victory. The uneasy relationship between FIFA and the British Home Nations came to a head after World War I, when the Home Nations left FIFA after refusing to play matches with their former wartime enemies. Without a British presence, FIFA took up the organization of the Olympic soccer tournaments of 1924 and 1928, and then, in 1930, organized the very first World Cup.

While all of this was going on, the British held on to the belief that matches between the four countries that make up the United Kingdom was as “international” as anyone needed soccer to be. They refused to participate in any truly international tournaments, and dedicated themselves mostly to their “British Home Championship,” with the occasional friendly exhibition match against a continental team thrown in. It wasn’t until after the Second World War that the British teams decided to re-join FIFA. I’ll go into the details of this reunion in a later post, for now I hope I’ve properly set the table for England’s particular relationship to soccer. It is defined, first and foremost, by a sense of ownership that fuels the belief that, because they invented the game, they ought to be the best at it. As we get deeper into World Cup history, we will see this belief tested, pierced, and even broken, and we will see how this recurring frustration has shaped the narrative around the English national team, which continues to strive to live up to their self-imposed expectations.

When the British teams re-joined FIFA, the rest of the world had to accept the fact that, since they had been separate from the beginning, England, Scotland, Wales and (Northern) Ireland were each going to have their own national team to represent them at international competitions. That is why, to this day, there is no such thing as a “United Kingdom” national team, and each of the countries that make up the U. K. compete individually at the World Cup, as well as any other International Tournament2. Meanwhile, the Home Championship is no longer played today, though it did stick around for a good one hundred years - from 1884 to 1984. Its first ever winner was Scotland and the last edition was won by Northern Ireland. Nowadays, the English, Scottish, Welsh, and Irish dream of lifting the World Cup instead.

That’s all for now, but come back next time and you will be reading about Soccer’s arrival in South America, the unlikely country that became the first international soccer sensation, and the creation and first installment of the World Cup.

We actually know the exact time and place Rugby and Soccer went their separate ways: “at the Freemason’s Tavern in Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London, at 7:00 p.m. on December 8, 1863, carrying the ball by hand was outlawed” (Wilson, Inverting the Pyramid)

The Olympic committee does not respect this deal, however, and so the Home Nations do not compete at the Olympics. There was one exception made, though, for the 2012 London Olympics where a Great Britain team was allowed to play the Soccer tournament. The team was made up of only English and Welsh players, as the Scottish, true to their character, refused to go along with the plan and the Northern Irish shrugged, knowing they weren’t gonna pick any of their players anyway.